Legal Dimensions of China-Philippines Dispute

This analysis was originally published by the International Bar Association

China and the Philippines have reached a critical juncture in their dispute over territory in the South China Sea. The case brought forth by the Philippines is now being looked at by an arbitral tribunal at The Hague – which will determine whether the case has enough merit to be heard.

Manila’s argument rests on challenging China’s sovereignty claims under Article 287 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which both China and the Philippines are state parties.

Tensions in the South China Sea have risen dramatically over the past year as China tries to alter the status quo through massive land reclamation and island construction activities.

Beijing’s land reclamation strategy in the South China Sea has escalated at such a pace that Washington has accelerated its efforts to seek a diplomatic and multilateral resolution.

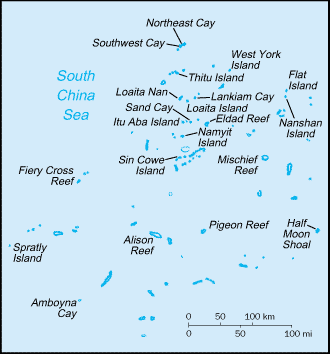

China’s creation of artificial islands in the Spratly Islands has resulted in a public showdown through which the US has accused China of attempting to force its way to de-facto control in the disputed seas.

President Barack Obama has been frank in his assessment of Beijing’s strategy: ‘Where we get concerned with China is where it is not necessarily abiding by international norms and rules, and is using its sheer size and muscle to force countries into subordinate positions.’

These comments were put even more bluntly by Admiral Harry Harris, commander of the Pacific Fleet, who remarked earlier this year that China ‘is creating a great wall of sand with dredges and bulldozers’.

As China increases its land reclamation activities in the South China Sea, there is a loose coalition – led by Washington and its regional allies – that is upping the stakes in an effort to deter Beijing from coercively changing the status quo.

The Philippines – a US treaty ally – is among the principal countries at loggerheads with China.

James Manicom is a maritime expert formerly with the Centre for International Governance Innovation. ‘From an international relations perspective, the case is very important,’ he says. ‘So, is the move a futile one by the Philippines? Yes, if we expect China to abide by the decision. However, there are other significant benefits to the Philippines, including winning friends among neighbouring states and in Washington.’

The recent spike in tensions came earlier this year with the release of several high-definition satellite images of land reclamation and construction on Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands, whose sovereignty is disputed by China and the Philippines.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has released several photos chronicling Beijing’s rapid expansion and construction of infrastructure on Mischief Reef, Fiery Cross Reef and several other reefs in the Spratlys.

Apart from the legal implications, the US approach to the issue is being watched closely by its allies and partners in the region.

‘This could be important as American power wanes and the debate picks up in the US about what US interests are a stake in East Asia,’ Manicom says.

‘Proponents of a robust US military and diplomatic presence in East Asia can point to the importance of rule-of-law-abiding allies like the Philippines as well as to traditional US interests like defending treaty allies on principle and protection of the freedom of navigation.’

Hans Corell is former Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs at the United Nations and Co-Chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute. ‘The disputes relating to territory and maritime boundaries in the South China Sea are extremely complex and international law requires that disputes are settled peacefully,’ he says.

In the 1980s, Corell was chairman of Sweden’s delegation that negotiated and concluded agreements on the maritime boundaries with three neighbouring states in the Baltic Sea. And during his ten years as the UN Legal Counsel, one of his tasks was to supervise the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law the Sea.

He is, therefore, familiar with the law that applies here, notably the United Nations Convention on the Law the Sea, and the manner in which disputes relating to the territorial sea, the Exclusive Economic Zone and the continental shelf should be settled. ‘In this case,’ he says, ‘the situation is complicated by the fact that there are also territorial disputes. Such disputes must be settled first, since territory is a determining factor for maritime delimitation.’

The decision on whether the Hague arbitration will proceed is expected next year and will have significant knock-on effects for the region and international law.

Richard Javad Heydarian, professor at De La Salle University in the Philippines, explained: ‘If the arbitral tribunal turns down jurisdiction, and refuses to even hear the merits of our arguments, then the very viability of international law as a conflict management/resolution mechanism will come under question. At the same time, if it decides to push ahead and eventually rule against China, then there is a huge risk. After all, there are no multilateral compliance enforcement mechanisms to force China — a permanent member of the UN Security Council — to abide by any unfavourable verdict.’

Related posts:

Category: FOREIGN POLICY & SECURITY, INTERNATIONAL LAW & HUMAN RIGHTS, POLITICS, REGIONS, SOUTH ASIA & ASIA PACIFIC